ENVIRONMENT: 54 Quebec deaths send warning signal

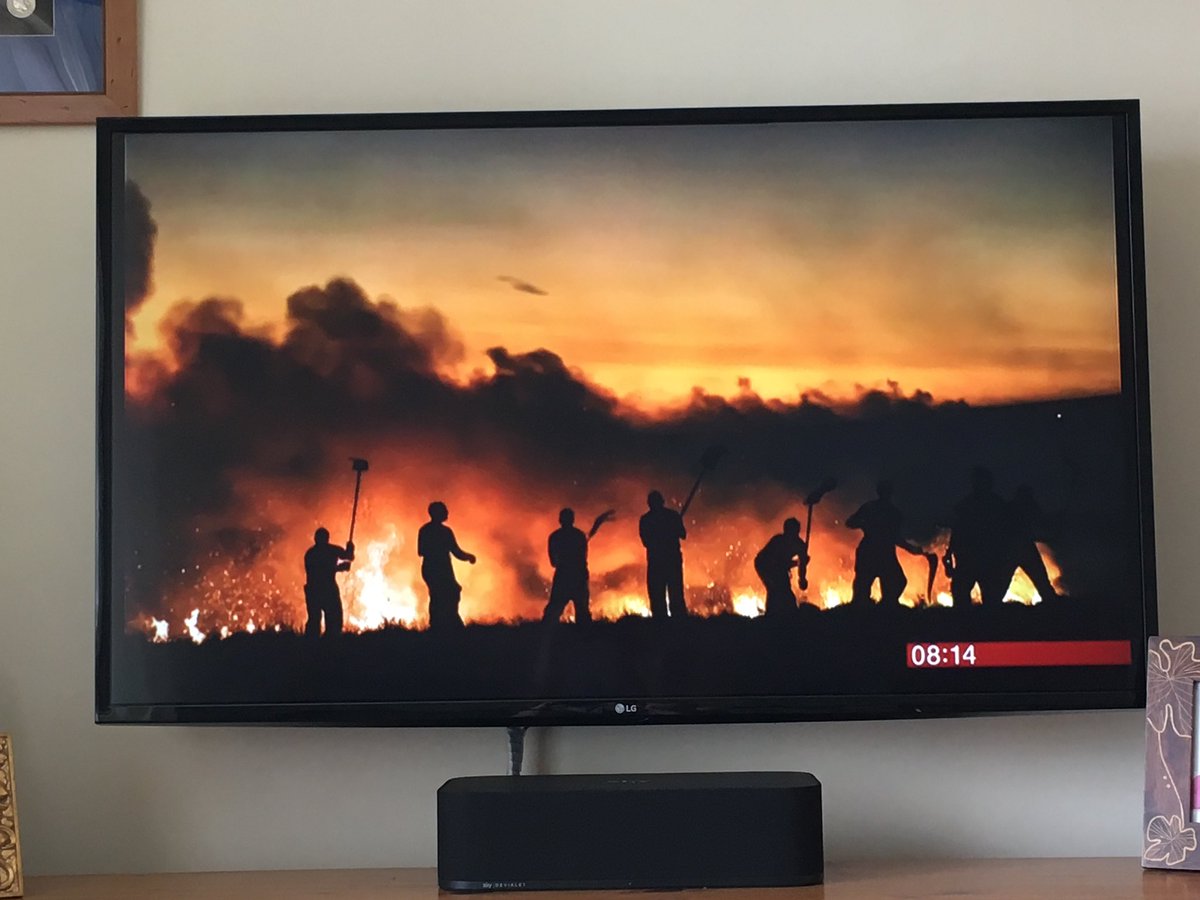

Local citizens help fight UK moreland fires

By Simon Lewis

Much of the world is in the grip of a heatwave. Britain is so hot and dry that we have Indonesia-style peat fires raging across our moorlands. Montreal posted its highest temperature ever, with the deaths of at least 54 people in Quebec attributed to the scorching heat. And if you think that’s hot and dangerous, the town of Quriyat in Oman never went below a frightening 42.6C for a full 24 hours in June, almost certainly a global record. While many people love a bit of sun, extreme heat is deadly. But are these sweltering temperatures just a freak event, or part of an ominous trend we need to prepare for?

Earth’s climate system has always produced occasional extreme weather events, both warm and cold. What is different about now is that extra short-term warmth – from the jet stream being further north than usual – is adding to the long-term trend of rising global temperatures. The warming trend is very clear: the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that all 18 years of the 21st century are among the 19 warmest on record; and 2016 was the warmest year ever recorded. Overall global surface air temperatures have risen by 1C since the industrial revolution. It is, therefore, no surprise that temperature records are being broken. And we can expect this to become a feature of future summers.

The long-term warming trend is driven by the release of greenhouse gases, chiefly carbon dioxide. Many alternative causes have been tested by scientists: the effects of sunspots, volcanic eruptions and other natural events. Only greenhouse gas emissions, dominated by fossil fuel use, explain the warming over the past century. This understanding isn’t just retrospective: 30 years ago this summer, climate scientist James Hansen told a US Senate committee that the climate was changing and fossil fuels were the main culprit. He made headlines worldwide with predictions that if emissions continued our planet would continue to warm, which it inexorably has.

Today’s heatwave is not related, as some have suggested, to the every-few-years shift of Pacific Ocean currents that affects global weather patterns, known as El Niño. A new modest-sized El Niño is predicted for later this year but is not yet detectable. Today’s heatwave is what is expected as Earth moves to an ever warmer state. But it is worth watching the news for the coming El Niño later this year: if it turns out to be a large event, next summer could bring more extremely hot weather. And beyond that, as the climate warms, summer heatwaves will escalate in their severity.

So what is to be done? The amount of warming we see is directly related to the cumulative emissions of carbon dioxide. Stopping the warming requires moving to zero emissions of carbon dioxide. Despite the Paris agreement on climate change being designed to do exactly that, progress has been slow. Today 80% of world energy use is from fossil fuels. While the share of renewables is rising rapidly, so is energy use, meaning that globally, carbon emissions are flatlining, not declining. Commitments made so far under the Paris agreement show that we are on track for an additional 2C warming this century. Such large and rapid change will make it very difficult for societies to cope.

We will therefore also need to adapt. There is a lot we can do. At an individual level, we can cool our homes by keeping the curtains and windows shut on the sunny side of our house during the day to slow the rate at which it heats up, and then open windows at night to cool it down. We also need to keep a close eye on the very young and very old because they cannot regulate their temperatures very well, and suffer most in the heat. The major 2003 European heatwave killed 70,000 mostly older people. Changes to social care, for example, to attend to the needs of people who are vulnerable to high temperatures, can help avoid such death tolls in the future.

Climate change is a greater threat to the UK than EU directives, terrorism, or a foreign power invading

Beyond this, many aspects of society will require deep and difficult changes, including to our own mindsets. In the summers of the future, particularly in the south of England, we will regularly live in Mediterranean-type conditions. Adapting our national infrastructure, particularly around maintaining our water supplies, updating our housing stock as it is built to retain heat, and altering how we manage our land to avoid further catastrophic fires, will all be required. It is under-appreciated that climate change will transform the very fabric of the experience of living in the UK.

This coming new reality is not high on the political agenda. Climate change is a greater threat to the UK than EU directives, terrorism or a foreign power invading. Yet the scope of our political discussion on future threats is limited to Brexit and spending on defence. Instead of this blinkered view where the future is the same as the past, we need to step out of the intense heat and take a cool look at what we are doing to our home planet.

The development of farming and rise of civilisations occurred within a 10,000-year window of unusually stable environmental conditions. Those stable interglacial conditions are over. Human actions are driving Earth to a hot new super-interglacial state. What scientists call the Anthropocene epoch, this unstable time, is a new chapter of history. Today’s heat is a forewarning of far worse to come. To live well in this new world needs political action to catch up with this changing reality. Fast.

Simon Lewis is professor of global change science at University College London and the University of Leeds. The article first appeared in the Guardian